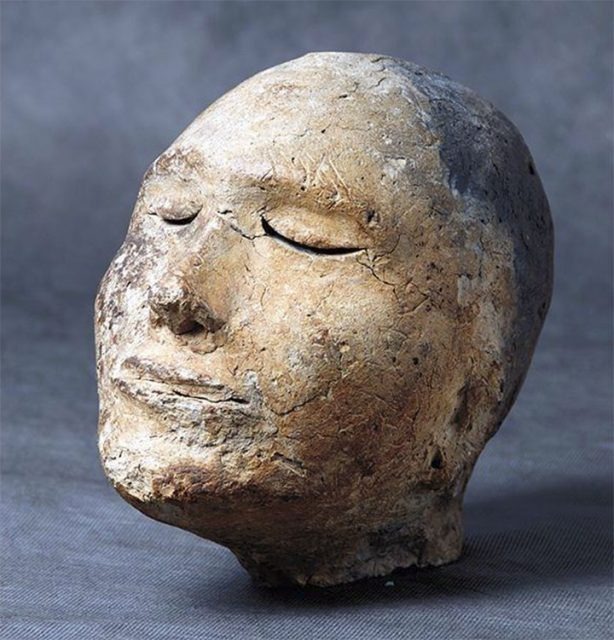

A life size clay head from ancient Siberia has revealed a ram’s skull inside a human-shaped shell! The head within a head was first spotted in the late 20th century but only now can its true nature be seen, thanks to modern techniques.

Made by the Tagar culture, who occupied the south of the region between the 8th – 2nd centuries BC, the death mask was discovered in 1968 at the Shestakovsky burial mound. This site is located in what’s now the Republic of Khakassia.

Archaeologist Prof Anatoly Martynov took credit for the find, which was “buried in a layer of red dead-burned clay” according to a 2010 piece in Science First Hand. X-rays illuminated a “small hollow space” inside, containing one freaky-looking skull. Getting inside the head wasn’t an option as the object had become too fragile over time.

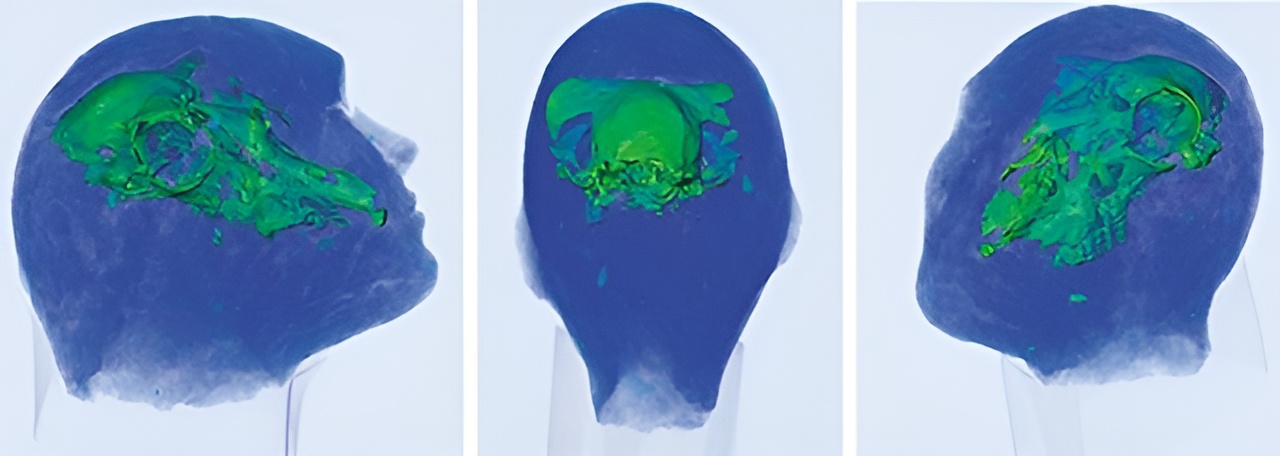

It’s taken decades to complete the bizarre picture. Even at the last minute, scientists were expecting to see a human skull within. Recent investigations using fluoroscopy, where x-rays capture internal images in real time, have shown the remains are in fact those of a ram.

Prof Natalya Polosmak (Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography in Novosibirsk, where the head is based) and Dr Konstantin Kuper (Institute of Nuclear Physics) were among those examining the artifact.

The 2,000 year old clay mask is thought to date from the Tesinsk period, or later stages of the Tagar culture. They were succeeded by the Tashtyk – interestingly, news broke last year of another such artifact, where an ancient face under a mask was finally unveiled using a CT scan.

As well as putting clay round corpse’s heads, it’s known the Tagar burned the dead in pits. The website Archaeology writes the Tagar individual, thought to be a young man, was “discovered among about 15 sets of cremated human remains”.

The pits were dug and built over it seems. Referring to the research of Dr Elga Vadetsakaya, the Siberian Times writes: “A log house was erected and covered with birch bark and fabrics”. This elaborate covering structure was “partly burned down and often the roof collapsed.”

Dr Vadetsakaya theorizes that a Tagar burial had 2 stages. The body was boxed up and left to decompose for a few years. After that the brain was removed via the ancient operating practice of trepanning. The skeleton was then wrapped in grass, leather and bark, creating a representation of its former owner.

For Vadetsakaya that’s where the clay came in. Was it important for the head to look like the deceased person? Apparently not. As Science First Hand writes, “Neither resemblance nor the face itself was of any interest” in ceremonial terms.

This was all done in preparation for funeral no.2. Evidence suggests bodies were left with the family of the departed, possibly for years before finally meeting their maker.

So where does the ram skull fit in? In Dr Vadetsakaya’s opinion, the man’s noggin may have perished. The animal head could be a makeshift replacement.

People who died in that time were expected to journey to the next life. Which is where the thoughts of Prof Polosmak come in. She thinks the ram-man took the place of someone who’s actual body was missing. Maybe the ram contained the person’s soul, enabling him to reach his post-death destination.

Speculation is rife about what exactly the man-meets-animal combination means. The significance of the ram in ancient societies probably plays a part here. Science First Hand mentions Khnum, the Egyptian god whose image can be that of a man with a ram’s head. Significantly, Khnum used clay to fashion various life forms.