At the turn of the 1970s, the great design rivalry between Bertone and Pininfarina reached an all-time high, with both companies seemingly determined to pull out all the stops to outdo one another. Bertone had perhaps opened the hostilities with the Marzal and with the first “wedge-shaped” supercar concept, the mighty Alfa Romeo Carabo. Italdesign had joined the fray with the Bizzarrini Manta and the Alfa Romeo Iguana. Pininfarina had replied using all its Ferrari firepower with the striking P5, the 512S berlinetta and the Modulo. The latter had caused quite a stir at the Geneva Motor Show in March 1970, yet nothing, not even the outlandish Modulo, could really have prepared visitors of the 1970 Turin Motor Show just a few months later to what they were about to see on the Bertone stand. The car was officially labelled “Stratos HF.” Nuccio Bertone had initially wanted to call it “Stratolimite,” as in “limit of the stratosphere,” clearly inspired by its space-age design. But after some time, it came to be known simply by its internal nickname: Zero.

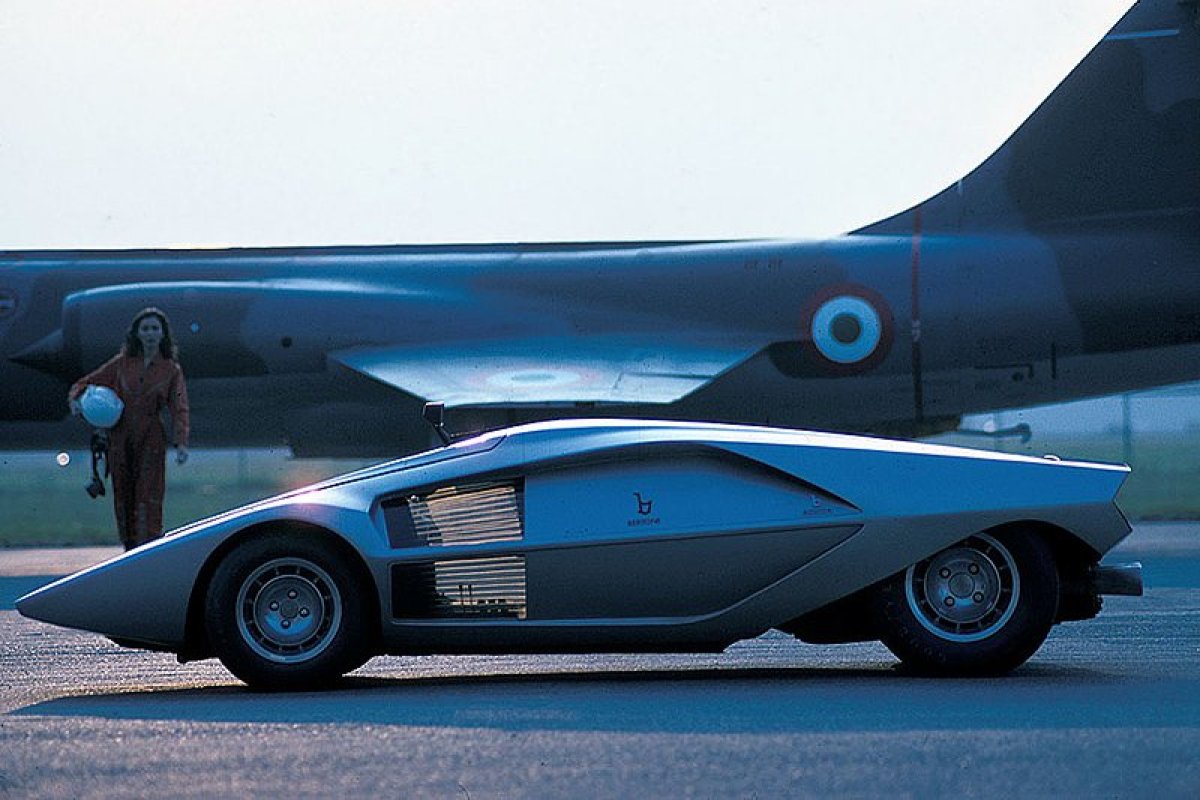

With the Stratos Zero, Bertone transcended the limits of automotive styling and chiseled a shape that appeared as though it were made of a solid block of metal, evoking speed and the sensation of travel. More remarkable still was the fact that the Zero was not only a design statement but a fully functioning prototype. There was a clear continuity of style and intent between the 1968 Carabo, 1970 Stratos and 1971 Countach prototype. The three projects showed a linear progression in formal research, to the extent that, randomly looking at the preliminary sketches done for each car and omitting the dates, it is difficult to tell which of those three projects they were for. If the Carabo was the radical dream car that broke new ground and the Countach the final step before production, the Stratos was a sculpture on four wheels if ever there was one, a true dream car that married concepts of architecture and pure artistic expression and applied them to the automotive object.

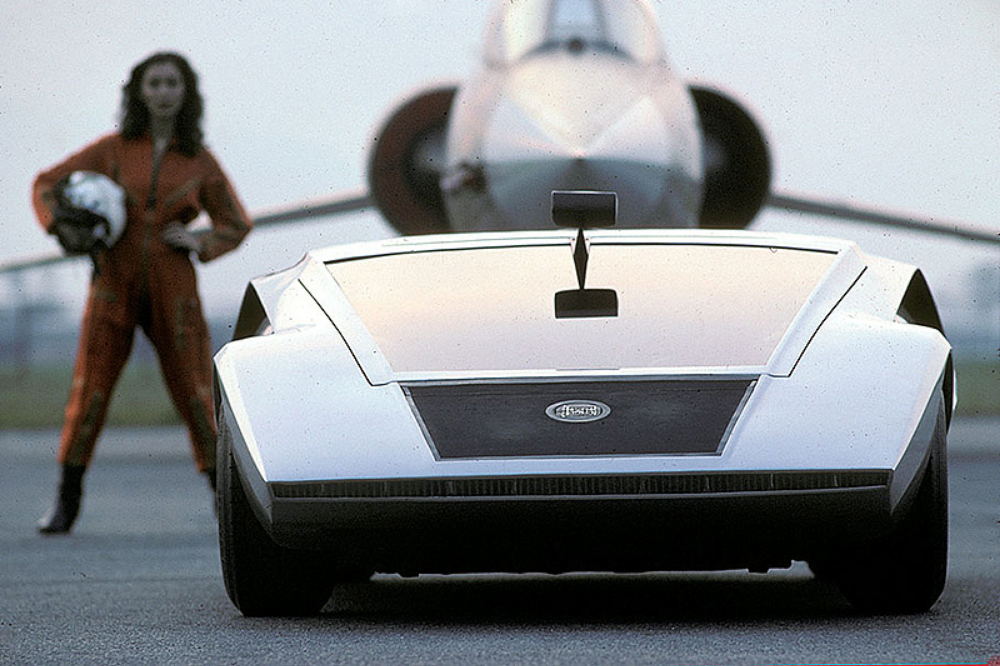

Everything about the Stratos looked futuristic. Its full-width row of ultrathin headlights made for a dramatic front view, echoed at the rear by the minimalist but highly effective combination of mesh grille, ribbon taillights, fat tires and dual exhaust offset to the side of the protruding gearbox case. The front headlight strip was backlit by ten 55W bulbs at the front, the rear strip by no less than 84 tiny bulbs spread all around the perimeter of the truncated tail. As for turn signals, the same lights simply lit up in succession from the centre to the edges!.

According to Eugenio Pagliano, who had joined Bertone’s styling studio a couple years earlier and would become its longstanding Interior Chief Designer, the initial concept behind the Stratos Zero for Bertone’s creative task force was simply to see how low a car they could build! Besides the tongue-in-cheek, slightly provocative aspect of this stated target, it made sense with regard to aerodynamics, where a minimal frontal section is always a prerequisite. It was possibly also a response to Pininfarina’s Modulo. Indeed, where the Modulo had been only 93.5 cm tall, the Stratos peaked at a mere 84 cm (33 inches) from the ground!.

The Zero was assembled by sourcing from existing Lancia parts. The efficient, no-nonsense mid-ship mechanical layout followed almost effortlessly from that height target, and the diminutive yet spritely 1.6-liter Lancia V-4 engine of the Fulvia HF was chosen for its minimal size as part of that quest for a sleek profile. The chassis was crafted onsite, and the engine was sourced, complete with its own sub-chassis and suspension, from a Fulvia coupé that had been involved in an accident, unbeknownst to Lancia. The double-wishbone with transverse leaf spring arrangement at the rear was simply the Fulvia’s front axle. At the front, the wheel fairings which dominated the narrow cabin were just wide enough to accommodate short McPherson struts. Disc brakes were fitted on all four wheels. A 45-liter fuel tank found space in the right side of the engine bay, and twin fans assisted radiator cooling. The spectacular triangular engine cover incorporated slats shaped to direct air towards the radiator, which was set all the way to the rear.

The cabin was so far up front that access was by way of a flip-up windscreen, and a sourced hydraulic linkage was devised so that, as the steering column was pushed forward to enable access to the driver’s seat, the windscreen would lift. The black rectangle at the bottom of the windscreen was in fact a small rubber mat intended to make climbing in easier by first stepping onto the bodywork. The Lancia badge at the centre of the mat cleverly concealed a pivoting handle that popped the windscreen open.

Certainly the seating position was as horizontal and as close to the ground as it could possibly get. With the two occupants sitting between the front wheels, the car could have hardly been any narrower as well. Once seated, the driver had nothing but the road in front of him and the sky above him, with a futuristic instrument panel offset to the side behind the front wheel-arch. Its graphics, hand-etched in the green Perspex, were certainly futuristic looking but probably difficult to concentrate on at any speed! Headroom was adequate for the average-sized driver, but one felt slightly “compressed” with the fully enveloping windscreen closed.

The steering wheel was made by Italian manufacturer Gallino-Hellebore. Rear-view mirrors sunk inside the side scallops allowed for somewhat limited rear vision. A small overhead mirror was occasionally installed for road tests atop the windscreen! In this extremely tight package, room for a spare wheel and luggage was found right behind the driver. The “chocolate bar” pattern of the seats themselves was carried through to the Lamborghini Countach LP500. The top side-windows slid backwards into the bodywork, while a “pop-up” wiper was concealed underneath a trap door at the base of the windscreen. Overall, the cost of building the Stratos Zero in 1970 was reportedly 40M Lire (equivalent then to $65,000 or roughly $444,000 in today dollars), when a brand new Lancia Fulvia Rally 1.6 HF coupé cost 2.25M Lire.

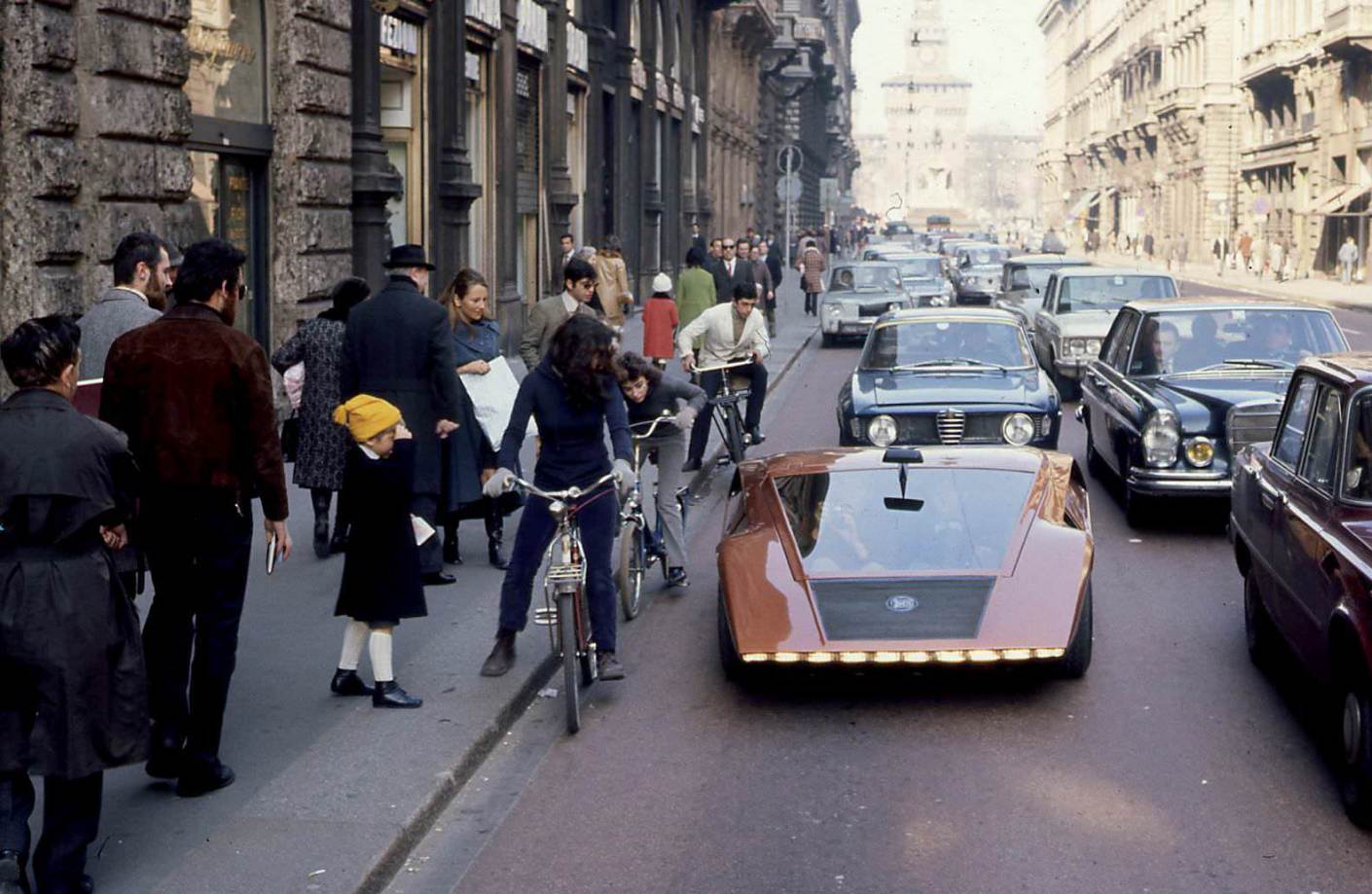

Despite being a very abstract vision of the automobile, Italian magazine Quattroruote actually took the Stratos prototype on the road back in 1971, driving it from Milan’s beltway to the historic town centre in front of the Duomo, where it caused, as one could only imagine, quite a sensation. The driver must have felt a certain degree of insecurity looking up at scooters as well as all other forms of traffic, dwarfed by trucks and buses passing by…

Nuccio Bertone had personally already driven the car on public roads when he went to meet Lancia’s top brass a few months earlier to discuss a more realistic sports car project which eventually became the Stratos Stradale. On that occasion, it is reported that the car passed underneath the closed entrance barriers at Lancia’s racing team headquarters, which earned it a most positive reception!

“One morning late in February 1971, Ugo Gobbato, the then chairman of Lancia, telephoned me,” Bertone recalled years later. Gobbato wanted to see the car – and that very afternoon Bertone drove it personally to Via San Paolo, headquarters of the Lancia works racing team. “I drove up to the main gate, where an astonished Lancia gatekeeper stared motionlessly at that strange object which was so low it could pass beneath his barrier. Meanwhile the rumble of the engine [at that time a Fulvia V4] had brought all the Lancia racing team people who were waiting for us out into the yard. Then the gatekeeper raised the bar. It was an unforgettable entrance. In the middle of the crowd I switched off the engine and climbed out of my ‘spaceship’.” Bertone was rapidly signed up to build a practical rally prototype.

It would be a wild exaggeration to say that the Stratos that eventually made it to showrooms bore much resemblance to the original prototype, but without the Zero, the car that would become one of rally racing’s most memorable icons would likely never have been.