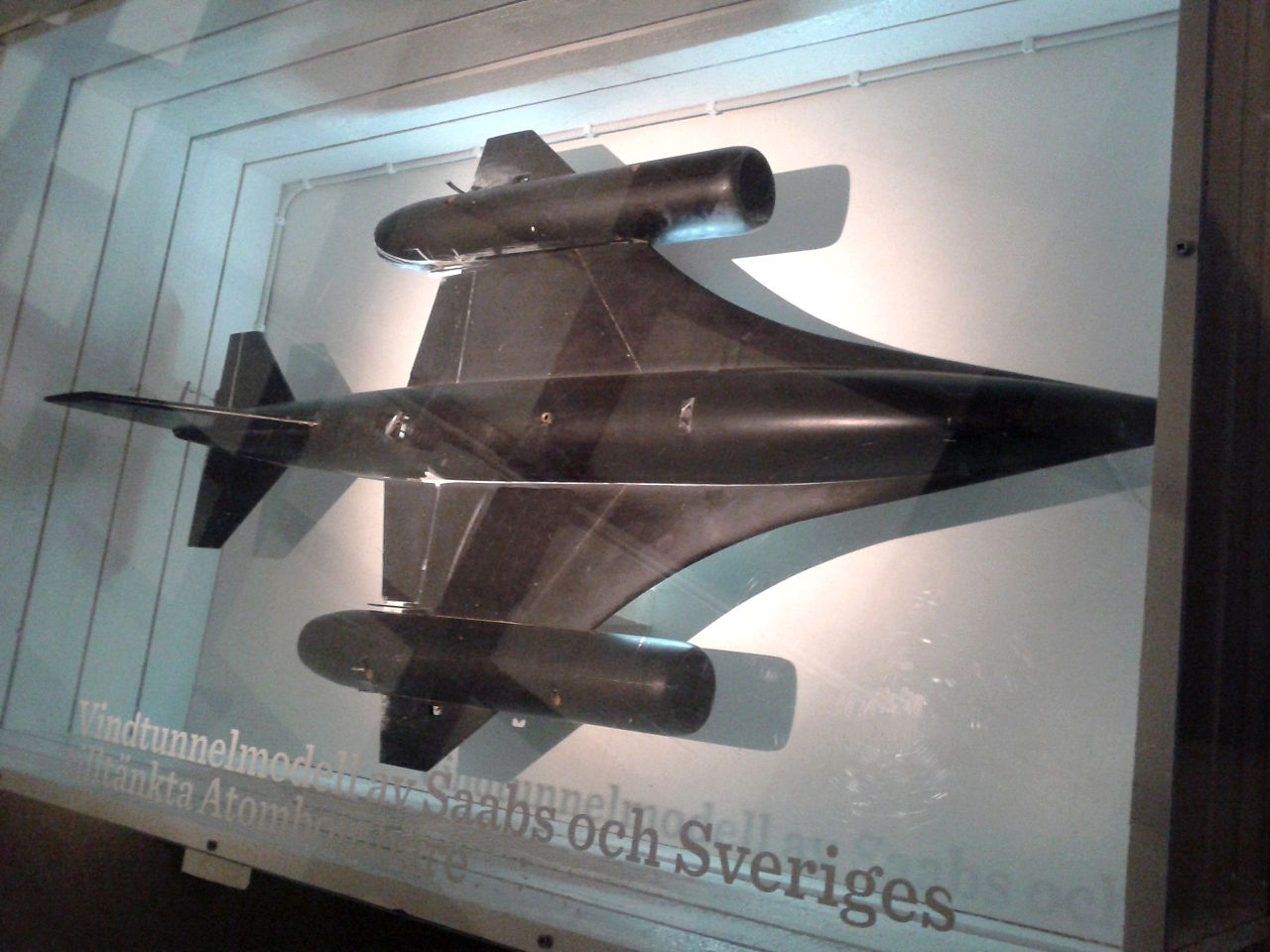

Swedish aircraft are a breath of fresh air. Idiosyncratic, clever and unorthodox, they have often been the result of a different way of thinking and peculiarly Swedish needs. That such a small nation makes its own combat aircraft is a quirk of history. Sweden’s non-aligned neutrality policy, which lasted until 2009, had its roots in the calamities suffered during the Napoleonic Wars of the early 19th century. The disastrous results included a loss of over a third of Sweden’s territory, most notably Finland, were not soon to be forgotten. A policy of avoiding military intervention and international allegiances wherever possible began in the early 19th century. In the 1930s, fearing a second world war, Sweden massively increased its defence spending. The War showed that neutrality was not always easy or carried out to the letter. In World War II, Sweden made itself very unpopular with the allies by supplying large amounts of vital iron ore to Nazi Germany, though Sweden was also exporting significant quantities of ball bearings to the Allies. There were trade agreements between Sweden and the Allies for these purposes, and during the latter parts of the War this included limiting Swedish exports to Germany (once Germany was too weak to pose a significant threat to Sweden anymore). Such is the delicate complicated position of non-alignment. This policy of ‘armed neutrality’ required indigenous armaments to avoid dependence or allegiance to a foreign power. From the mid-1940s Sweden’s Försvarets forskningsanstalt (FOA) intended to develop it own nuclear deterrent, an ambition it chose to give up when it joined the non-proliferation treaty in 1968.

It was the smallest nation, in terms of both population and economy, to design and build its own advanced military aircraft. But there are shades of ‘indigenous’ as no country other than the US and Russia (and lately China) has access to the full spectrum of technologies required to make a modern fighter. The Gripen, for example, uses a British ejection seat, an (essentially) American engine, pan-European air-to-air missiles and a German gun. The reliance on US tech has enabled the US to block export licences in order to scupper several potential Saab exports that threatened US sales, most notably Indian interest in the Viggen in the 1980s.

Let’s head North to the icy beauty of Sweden to choose twelve incredible Swedish aeroplanes.

Saab 21 (1943)

There are reasons that propellers are at the front, and most of them relate to that being the way engines are designed to turn them. The perils of the pusher are such that the US Army banned pusher designs in 1914. Shame though, as a pusher means you can have your guns very easily placed on the centreline, a shorter fuselage and a greatly improved view for the pilot.

The Saab 21 did not have a spectacular performance; 400 mph may have been insanely fast in 1940, but by 1945 when the J 21 entered service it was decidedly mediocre. To avoid a diced pilot, an ejection seat was required, the J 21 being the first non-German aircraft to carry an ejection seat as standard. The aircraft was well-armed, with one 20-mm cannon and two 13.2mm heavy machine guns in the nose and two more heavy machine-guns in the wings.

Powered by the Daimler-Benz DB 605 that had powered the cream of axis inline fighters, the J 21 was hampered by the war ending and the 605 line ending. Intriguingly, there were plans for a more advanced version with a Rolls-Royce Griffon and a Mustang-style bubble canopy, these never happened as the jet age had arrived. The J 21 become part of one of the very rarest aircraft breeds, those that went from piston to jet propulsion as the J 21R.

Saab B 17

No, not that one. The B 17 was Saab’s first aircraft and Sweden’s first indigenous ‘modern’ stressed-skin monoplane. Unusually conventional by Saab standards, the aircraft had already been designed by ASJA, the catchily named AB Svenska Järnvägsverkstädernas Aeroplanavdelning (Swedish Railway Workshops’ Aeroplane Department) thus joining the likes of the Henschel 129 and the English Electric Lightning in the surprisingly crowded pantheon of aircraft built by railway locomotive manufacturers. The B 17 was a workmanlike design that compared well with contemporary single-engine light bombing aircraft. And if you think it looks particularly similar to US designs of the era, the fact that between 40 and 50 American engineers were employed by ASJA on its development might not come as a total surprise. Intended for the dive-bombing role, the B 17’s wing wasn’t up to the strain of this form of attack and required strengthening. Although subsequently cleared for diving attacks, the B 17 was limited to a shallow angle of dive for the rest of its career. Speed in the dive was limited by the large undercarriage doors which functioned as dive brakes when the B 17 made its attack and on the subject of undercarriage, the wheels of the undercarriage could be switched for retractable skis for winter operation. To add even more variety 38 examples of a reconnaissance floatplane version was also built.

Entering service in 1942 over 300 were built, most of the B 17 bomber version, with just over 20 of the S 17 reconnaissance aircraft also constructed. The Saabs remained in frontline service until 1950 though continued in second line roles for a further time, latterly as a target tug into the early 1960s. A potentially exciting aside occurred during the war when 15 B 17s were loaned to exiled Danish forces in Sweden to support a Danish invasion intended to liberate that nation from German occupation, known as Danforce. Thankfully the war ended before Danforce were committed to retaking Denmark, the Danish markings on the Saabs were painted out and the aircraft returned to Swedish control. Around the time that the aircraft was being withdrawn from Swedish service, 47 were bought for use by the Imperial Ethiopian Air Force. Ethiopian Saab 17s would be the only examples to fire their guns in anger, at least once, when several were used to attack a group of Somali criminals who had derailed and robbed a train. The Saab 17 was operated by Ethiopia until 1968 and thus the last frontline examples of this Scandinavian aircraft saw out their careers under the African sky. Of five survivors, one example remains airworthy at the Swedish Air Force Museum at Linköping.

Saab JAS 39 Gripen (1988)

On 29 March 2011, the Swedish Air Force sent combat aircraft to war for the first time since 1963. Eight Saab Gripens supported by a Saab 340 AEW&C and a C-130 Hercules tanker were deployed in support of the No-Fly Zone over Libya. The small fighter-bomber performed well. Initially, it was tasked purely with counter-air, but NATO planners noticed the Gripen had a very capable reconnaissance pod (the SPK 39) and its responsibilities were accordingly widened.

A rather boutique operation, the Saab Gripen has seen a small factory create around 280 aircraft since the type first flew in 1988. It has served in unobtrusive numbers around the world for sensible air forces on a budget. It is considered by many to have the lowest cost per flight hour for a modern fighter, and is relatively easy to maintain. I spoke to a Gripen maintainer a few years ago and he complained of not having enough to do, he had come from a MiG background. It is comparable with a top of the range small car, coming with a wealth of high-end accessories which include one of the world’s best helmet display and cueing systems, the formidable IRIS-T infra-red missile and the well trusted ‘404 engine. Perhaps the most impressive ‘accessory’ is the long-range Meteor air-to-air missile, giving a bantamweight the reach of the heaviest heavyweight. Much of the Gripen’s magic comes from a wealth of invisible capabilities: its electronic warfare suite is extremely well-respected by pilots who have ‘fought’ against the Gripen in international exercises. The basic philosophy of the Gripen was to create the smallest possible aircraft that wouldn’t be laughed out of a war with the Soviet Union. According to Tony Inesson, “Swedish defense planning also more or less assumed a NATO intervention. The Soviets never really considered Sweden a truly neutral power, but rather as being aligned with the West.” Building an air force that could take the USSR on its own terms was impossible, but one that could slow an invasion down until NATO leapt into the fray was possible. In the 1970s when what became the Gripen was first being considered Sweden’s defence planners had a big think. The cost of new, ever more complex, combat aircraft was generally spiralling out of control, one exception to this was the US F-16 which was smaller and lighter than the aircraft it replaced. Saab studied the F-16 with interest and wondered whether something even smaller might be able to replace its Viggens. Advances in materials and electronics, as well as engine technology, aerodynamics and flight control systems, enabled the Gripen to emerge as a bantamweight fighter with a hell of a punch. The new fighter, which first flew in 1988, was 6,000-Ib lighter than the Viggen and in aerodynamic form showed the future path of European combat aircraft. It was the first of a new class of canard-deltas, and has since been joined by the European Rafale and Typhoon, and the Chinese J-10 and J-20.

The next-generation Gripen will be the E (and two-seat F.) These are larger heavier aircraft powered by the F414, they are set to enter service soon.

(Some have argued that the Gripen’s use in Libya was largely a PR exercise to promote the Gripen for export, but Fredrik Doeser has argued that this view does not hold water as it could have been deployed to Afghanistan and the aircraft was already favourably viewed, something that could have been changed by any teething issues in its first combat deployment)

Saab 340

Had the Habsburgs stuck around long enough to get into the aircraft-making business, their offering would’ve been something like the Saab 340. It’s reliable and innovative, sturdy, loved for its handling and cost-effectiveness, loathed for its noisiness and its less-than-luxurious accommodations, lacking space for all its baggage (in the overhead bins, anyway), pretty to look at until you start adding military bits and bobs to it, and managing to stick around long after conventional wisdom deems it out of fashion. Sometimes it hears its name mentioned in a not-so-friendly way (though not due to any fault of the aircraft itself), but, at the end of the day, as regional airliners go, you could do a hell of a lot worse. After all, you don’t enjoy a nigh four-decade lifespan, hear your number called for hauling passengers and freight on three-hour hops to remote Alaskan airstrips, and get adapted for the maritime surveillance role (Japan Coast Guard) and airborne command and control (Swedish and Royal Thai Air Forces) if you’re not doing something right. The Erieye Airborne Early Warning and Control System fitted to the 340 AEW (among other airframes) has an AESA radar as its primary sensor and is widely considered world-class.

The 340 has gotten a lot of undue flak on the Internet, mostly from travel bloggers who seem to have severe allergic reactions to anything vaguely resembling a propeller, which is unfortunate, as it’s proven to be an excellent aircraft throughout its career, replete with forward-thinking technology like diffusion welding instead of rivets and, with the Saab 340B Plus variant, a noise and vibration reduction system (which, alas, came too late to help the poor 340’s reputation for being loud). It’s carried presidents and popes, and plenty of happy passengers.

The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes Vol II will be a fantastic sequel to The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes Vol 1. As soon as it reaches 100% funding, work will begin and what an incredible book we have planned. Click on the image below to pre-order.

The extended version, the fifty-seat Saab 2000, had the misfortune of coming on scene just as airlines were transitioning over to regional jets, and only sixty-three were built. As for the 340, production capped at 459 airframes, and, while there’s a trend among the major air carriers moving away from aircraft in the 340’s capacity category (generally 34 to 37 seats), and the 340 is getting up there in years, the type can still be found with about forty airlines and air arms. Regional turboprops might lack the sex appeal of fast jets like Drakens or Viggens or Gripens—though I should reiterate that, military variants notwithstanding, the 340 is quite a cute little fellow—but the 340 has certainly done more than enough to earn a place on any list of Sweden’s finest flying machines.

The extraordinary beautiful Hush-Kit Book of Volume 2 will begin when funding reaches 100%. To support it simply pre-order your copy here. Save the Hush-Kit blog. Our site is absolutely free and we want to keep it that way. If you’ve enjoyed an article you can donate here. Your donations keep this going. Treat yourself to something from our shop here. Thank you.

Saab 37 Viggen

It is said that Sweden could either afford the Viggen or the bomb, but not both. Sweden chose the Viggen and gave up its nuclear ambitions. Clint Eastwood asked for the Viggen to star alongside himself in his wild 1982 Cold War espionage thriller Firefox. The aircraft would have played the futuristic MiG-31 ‘Firefox’. On looks alone, can you blame Eastwood? The Viggen looked like the future, and in many ways it was.

The first thing you notice is the configuration. Aside the kidney-shaped air intakes, ahead of the main wings are a small set of ‘wings’ known as canards. Canards had been fitted on the American XB-70 Valkyrie bomber, the Mikoyan-Gurevich Ye-8 and a few other experimental types, but the Viggen was the first modern canard-equipped aircraft to enter service. Unlike later canard-deltas, these were not all-moving, but they were fixed with a moving trailing edge flap. Not only do they render the Viggen, arguably, a Mach 2-capable biplane but they do other, more tangible, things. The Viggen also has an unusual wing shape. Having two angles of leading-edge sweep-back (the ‘kink’ or ‘dog leg’) allows for greater amounts of more stable lift from a wing of less relative area. This happens because the change in leading-edge angle keeps lift-generating air vortices from originating at the wing root. The earlier Draken and (later mark) Vulcan also featured rather different kinky deltas. India’s Tejas fighter has opted for a similar wing design solution to the Viggen.

Short-take off and landing was a key requirement for the type. To stop the aircraft without the fuss and hazards of a brake chute, an impressive thrust reverser mechanism – unique on a combat aircraft at the time, was added. Consisting of three triangular steel plates, it was closed up to redirect engine thrust forward through the side slit below the tail. The pilot could actually reverse his machine on the ground without the aid of a ground vehicle. Most famously, and a Swedish air show perennial, the Viggen could do a fast touch-and-go manoeuvre in which it would come in hot, arrest itself on landing with reverse thrust and then via a so-called Y-turn change the direction it was facing and rip right back into the sky on afterburner. All in a few seconds! Try that in a General Dynamics F-111. The Viggen was expected to operate from 500 to 800 metre lengths of motorway or damaged bases and be readily looked after by reservists and conscript groundcrew. It had fairly tall tandem main landing gear with anti-lock brakes. The Viggen almost seemed to handle like a sports car on the ground.

Video: Saab JAS 37 Viggen Svenska flygvapnets vägbaser

That was far from the only innovation in the Viggen: at the heart of the Viggen’s system was the CK 37 central computer (Central Kalkylator 37), the world’s first airborne computer to use integrated circuits. Many nearly boutique-level design touches were incorporated all across this aircraft’s systems. The earlier Saab 35 Draken was intended for the same ground-controlled, high altitude missile interceptions of the Convair F-102/106 or the Sukhoi Su-15; the JA 37 fighter variant of the Viggen embodied a dark recognition that future armed conflict might be a little more dirty and tactical – and require greater intelligence.

The Viggen came in five flavours: the AJ37 attack version, SK37 two-seat trainer, SH- and SF37 reconnaissance variants and the final version, the JA37 fighter-interceptor.

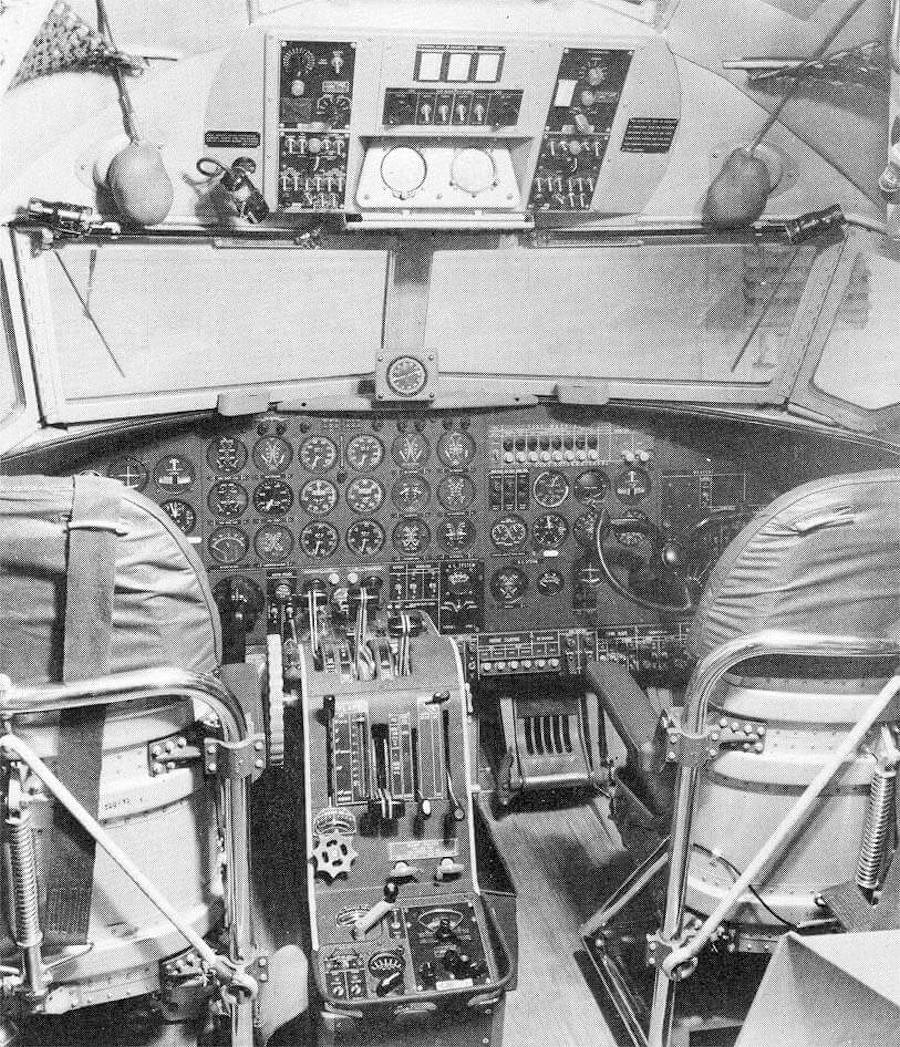

The Viggen had an impressive early example of a centralized computer to support the pilot by integrating and partly automating tasks such as navigation and fire control. The Central Kalkylator 37 was connected to a head-up-display and an X-band radar set. This gear meant the Viggen could meet a requirement for single-pilot operation. Performance metrics would also have been impaired thanks to the weight and space requirements of accommodating a second crew member so the dependence on technology was vital. The Viggen is most often celebrated for its out-of-the-box structural engineering but its avionics package ultimately is what made it the right investment for the Flygvapnet into the 2000s.

The Viggen was so clever in so many ways.

Its vertical fin could be folded down with dispersal to hardened bunkers or caves in mind? The outdoorsy Swedish jet made some of its Soviet and Western contemporaries look like precious hangar queens dependent on massive budgets and large, vulnerable air bases. In the Viggen, Sweden was able to extend the achievements of the Draken program and impress the world. A high-intensity R&D programme – fully funded and supported by the Swedish government – and a national flair for industrial design, combined with the employment of U.S.-licensed engine brought forth a winner.

With its funky pusher propeller fighters, crazy double deltas and early adoption of the canard for jet fighters, it is difficult to accuse Saab of being a slave to convention. Thus at first glance, their only twin piston-engine bomber, the B 18, looks disappointingly ordinary, sort of halfway between a Ju 88 and a Hampden. But this elegant twin rewards a closer look as its arguably humdrum appearance was somewhat deceptive. First off, the cockpit is offset to the left, and as anyone who has ever glanced at a Sea Vixen or a Canberra PR.9 knows, offset cockpits are cool. Secondly, despite looking rather outdated considering it entered service in 1944, its performance was distinctly impressive with a top speed only 20 km/h slower than the vaunted de Havilland Mosquito FB.VI despite carrying three Swedes rather than the mere two of the Mosquito, one of whom got to wield a defensive machine gun. The Mosquito similarities didn’t end there: limited numbers of both (18 Mosquitoes and 52 Saabs) were equipped with a large calibre gun for the anti-shipping role. Weirdly both aircraft went for a 57-mm weapon.

And both aircraft were effective multi-role platforms before multi-role was really a ‘thing’ and could carry a vast array of different weaponry. The Saab however was never developed into a night fighter, for that role the Swedish used the J 30: which was their designation for the Mosquito! Most surprising of all perhaps is the fact that this fairly normal-looking WWII medium bomber was fitted with ejection seats. Sadly this was due to the Saab 18 garnering something of a reputation for crashing by the late 1940s. Ah well, the dangerous planes are always the most exciting right? For a Swedish aircraft the Saab 18 also pushed the envelope when it came to Sweden’s famed neutrality. In the reconnaissance role, B 18s were utilised during 1945 and 46 to overfly Baltic ports and photograph all Soviet shipping they found. In the course of these missions the Saabs were routinely subject to interception attempts by Soviet fighters but their speed rendered them essentially invulnerable, notably unlike other aircraft operating as spyplanes – Sweden lost an ELINT C-47 to Soviet fighters in 1952, then the search and rescue Catalina they sent out to try and find the missing aircraft was shot down too three days later sparking a major diplomatic incident. The B 18 remained in service until the late ‘fifties with the reconnaissance variants the last to be retired in 1959, replaced by another cool-looking Saab product (of course), the Lansen.

Saab 29 Tunnan (1948)

Aren’t Tunnans Brilliant. It’s 1948 and Europe’s aircraft manufacturers are busily reading captured German documents to learn about swept wings. But while Hawker and Supermarine are messing around with attaching them to a couple of spare airframes for research purposes, SAAB are test flying Europe’s first non-fascist swept wing production fighter. By 1951 the J29 Tunnan is in squadron service while the RAF are enduring the more pedestrian looking de Havilland Venom. To add insult to injury the shiny Swede used the same Ghost engine as the Venom to go faster, claiming two FAI speed records for the 500km and 1000km closed circuits. It could also carry 700kg more, which makes you wonder what de Havilland were doing. By 1954 the J29 had even gained an afterburner, one of the first aircraft to do so. But beating the low hanging fruit of de Havilland’s difficult second jet fighter isn’t all the Tunnan has going for it. SAAB’s most produced aircraft with 662 built, it served until 1967 as a front-line fighter and was still in use as a target tug until 1976. It was also the only SAAB to date to see combat helping with peacekeeping efforts in the Congo under the control of the United Nations. This saw 9 J29Bs and two S29C photoreconnaissance aircraft adorned with UN markings, literally just a big U and N painted on the fuselage, and operated by F22 Wing of the Swedish Air Force. Despite taking ground fire on numerous occasions while carrying out strikes on secessionists and mercenaries no Tunnans were lost in combat. Ironically after surviving the civil war all but four were then destroyed at their base in 1963 as it wasn’t considered cost-effective taking them back to Sweden. Objectively good looking and a technological trail blazer*the Tunnan is a brilliantly packaged little fighter, just look at how the landing lights drop down from the nose and the main gear tucks into the fuselage. The J29 also fitted an ejector seat before they became de rigeur.

FFVS J 22 (1942)

By 1940, the fighter component of the Flygvapnet consisted mostly of the Gloster Gladiator (designated J 8 in Swedish service) which were looking increasingly old hat when compared to the latest monoplane fighters busily shooting each other down all over Europe. In an attempt to maintain a credible defensive force Sweden ordered large numbers of the Seversky P-35 and Vultee P-66 Vanguard from the US only for the Americans to slap an embargo on the export of all arms to any country except the UK after only 60 P-35s had been delivered. To be fair this may have been a blessing in disguise as the P-35 (J 9 in Sweden) was a pretty woeful fighter. Sweden looked around for a replacement and intriguingly considered the Mitsubishi A6M Zero amongst others (concern about the practicality of delivery put paid to that idea). Orders were ultimately placed for the outdated Fiat CR.42 (J 11) and Reggiane Re.2000 (J 20) but neither was considered entirely satisfactory and the decision was taken to manufacture a fighter domestically instead. Sweden’s only major aircraft company, Saab, had their hands full manufacturing the B 17 (not that one) and B 18 so, impressively the Swedish government created a firm and factory from scratch specifically to design and build a new fighter: the Kungliga Flygförvaltningens Flygverkstad i Stockholm (“Royal Air Administration Aircraft Factory in Stockholm”) shortened to FFVS. From the start the aircraft was intended to be relatively light and simple and to utilise the reliable Pratt and Whitney R-1830 Twin Wasp which was also the engine of the Seversky P-35/J 9. Unfortunately Sweden had no means to procure any more R-1830 engines from the US due to the embargo and no spare engines had been delivered with the batch of Seversky fighters that had been delivered. Therefore the Swedes elected to copy the engine and start production domestically, no small undertaking in the absence of any plans or drawings. The unlicensed Twin Wasp copy, designated the STWC-3, eventually powered most of the J 22s but the engine programme ran slightly behind schedule and to make up the numbers 100 R-1830s managed to be procured from the Vichy french regime. The purposeful looking FFVS J 22 was conventional in layout, apart from the undercarriage which was unusually narrow for its height and retracted into the fuselage in a unique arrangement. The construction method used was novel with plywood sheets cladding a steel-tube frame, the plywood skin being partially load bearing. The J 22 flew for the first time in September 1942 and considering this was the first fighter aircraft designed in Sweden since the Svenska Aero Jaktfalkenof 1929 and that the engine was of significantly lower power than was considered necessary for a fighter by other nations in 1942, it turned out to be a remarkably good aircraft. Intended to roughly match the performance of contemporary Spitfire and Bf 109 models when the design was finalised, designer Bo Lundberg had admirably stretched what was possible with the limited power of the R-1830 to achieve just that. With barely more than 1000 hp available from the STWC-3, the J 22 possessed decent performance and its handling was highly praised by pilots.

Looking somewhat like an unholy union between an Fw 190 and an F8F Bearcat, the J 22 was touted as being the fastest aircraft in the world ‘relative to engine power’. Though this was not true (the Mark I Spitfire was faster still with an engine of roughly the same rated power output), the J 22 was no slouch, though it must be admitted that by the time the first of the 198 production J 22s entered service in October 1943 its performance was not quite level with the world’s best. Nonetheless, when tested in mock combat against the P-51D Mustang (J 26) after the war the J 22 could reportedly hold its own at low and medium altitude. The power of the Twin Wasp copy fell off abruptly over 15,000 feet and this was probably the type’s most serious flaw. Its armament was also underwhelming, initially two 13.2mm (0.52in) Akan M/39A and two 8mm machine guns, later aircraft had four 13.2mm guns which was better (but still somewhat lacking).

The J 22 makes for an intriguing comparison with two other aircraft produced by nations with limited fighter experience, Australia’s Commonwealth Boomerang and Finland’s VL Myrsky. All three were designed and built to make up for an uncertain supply of foreign designs, were intended to be simple to build and maintain, all used the R-1830 Twin Wasp and all three were surprisingly effective. The J 22 was the fastest of the lot and proved popular and reliable, had it been produced in a different time by a nation not categorically wedded to the idea of neutrality, it may well have proved a successful export, being quite fast, simple, and reliable. As it was the J 22s served Sweden until 1952 and arguably more importantly gave the Swedish Aircraft Industry invaluable experience that it would put to good use in the years to come. Three are known to survive, one in taxiable condition, and another is being restored to fly.

Saab 32 Lansen (1951)

Hermann Behrbohm was a German mathematician who had worked for the Messerschmitt aircraft company from 1937. He contributed to high-speed trials of the Bf 109 fighter, and the development of the Me 163 and Me 262. His colleagues included the great Alexander Lippisch, father of the modern delta wing. Behrbohm’s most influential work was on the P.1101 fighter series, conceived as part of the Jägernotprogramm emergency fighter programme of 1944. This unflown remarkable jet fighter design, with its nose-mounted air intake and swept wings would inform the post-war F-86, MiG-15 and the Swedish Lansen. Following the war, Behrbohm was much sought after by nations wishing to harvest his remarkable know-how. He chose to move and work in Sweden. His influence on the Saab 32 Lansen, an attack aircraft built to replace the B 18, saw the aircraft adopt an exceptionally clean aerodynamic form. It is said to be the first aircraft created with a fully detailed mathematical model of its outer-mold line. The aircraft was capable of supersonic flight in a shallow dive. Behrbohm would also work on the Draken and Viggen, notably on the latter’s canard-delta form.

Svenska Aero Jaktfalken (1929)

After landing the Jaktfalken, Swedish Air Force test pilot Nils Söderberg declared“this is the best aircraft that I have flown so far”. The influence of Germans in Swedish aircraft is a recurrent theme, the Jaktfalken is no exception, as it was designed by the German Carl Clemens Bücker (famous for his Jungmann and Jungmeister). It was a world-class fighter but was never ordered in numbers, it won a single export order from Norway, and by single we mean one aeroplane.

SAAB 90 Scandia (1946)

Many nations’ aircraft industries grew fat and strong from the glut of wartime orders, and aeroplane production reached an all-time high. Sweden was no exception. In fact, being neutral and mostly spared from heavy strategic bombing (apart from that one time the Soviets had a go at Stockholm) its industry needn’t worry about such trifling matters as production lines being reduced to dust and cinder. When the war ended, SAAB’s future became uncertain. What would they do without the threat of an imminent invasion motivating combat aircraft production on a massive scale? What would they do with all their employees in the factories and design rooms? The good folks at SAAB, decided the only sensible thing to do was to branch out into the civilian sector and create the other SAAB (Svenska Automobil Aktiebolaget) as well as putting the original SAAB (Svenska Aeroplan Aktiebolaget) to work building the most modern, comfortable airliner in the world: the SAAB 90 Scandia.

Carrying thirty passengers up to 650 miles at a 211 mph cruise speed and up to 279mph in a hurry, the Scandia featured novelties such as a tricycle landing gear, and an airfoil designed using NACA profiles. Its two 1820hp Pratt & Whitney R-2180-E twin wasp radial engines provided ample power, allowing a loaded Scania to take off on just one engine. This of course drastically improved safety, especially in the take-off and landing phases, safety was further enhanced by the superior pilot view provided by the tricycle gear. The Scandia improved upon all the best qualities of the 1930s era DC-3 which was the airliner at the time. Entering production in 1946, SAAB had a real winner on its hands.

Except there was one little thing the execs at SAAB had overlooked. Or rather, there were 10,781 things that they had overlooked. That’s how many DC-3s and C-47s were built in total and now that the war was over, they were being sold for practically nothing. There was simply no way for SAAB to compete with those kinds of numbers and it looked like the future was again dark for the Swedish aeroplane manufacturer. Luckily for them, the start of the cold war meant SAAB soon received an order for 661 J-29 fighter jets. The Scandia was put aside after a meagre 18 were built and fell into obscurity.

The SAAB 90 did fly for Aktiebolaget Aerotransport (ABA) from Sweden, but spent most of its career in the warmer climate of the jungles of Brazil, in the service Viação Aérea São Paulo S/A (São Paulo Airways) until 1969.

–– Sebastian Craenen

Saab 35 Draken (1955)

That the Draken was a decent candidate for the best fighter in operational service in 1960 is a huge accolade for Sweden, and the result of the nation’s extremely smart defence policy of the 1950s. The Royal Swedish Air Force realised that any chance of survival against a Soviet invasion depended on departing air fields at the first whiff of war and hiding in the sticks. It was apparent that large fixed airbases were easy to locate and attack, so the Swedish Air Force went ‘off-base’. The Draken was intended to employ an indigenous jet engine design, the STAL Dovern, which was tested on a Lancaster. But the British Rolls-Royce Avon, which would also power the Lightning, was deemed a superior choice.

The policy of domestic aircraft creation has always been extremely costly and vulnerable to cancellation by politicians seeking to save money. Whereas the US could afford cost overruns, Swedish aircraft projects were under a lot more scrutiny (this continues to the present day).

Though initially excellent, the J 29s introduced in 1951 would struggle to effectively counter the fast Soviet Tu-16 bombers coming into service in 1954. With excellent foresight, work on a faster replacement for the J 29 had begun before the Tunnen had even entered service. The next fighter was to feature a radical new wing design, a world-leading datalink and would be easy to maintain and operate from reinforced sections of motorway. It would also be extremely swift, at mach 2, around twice as fast as the J 29. This remarkable project seemed to be going extremely well –– and then along came Wennerström.

TT-helg-wennerström

Klockan är halv tio på förmiddagen den 20 juni 1963. På Riksbron i Stockholm går tre män fram till en fjärde, en vithårig man i ljus sommarkostym med vit skjorta och mörk fluga. En av de tre rycker honom lätt i högerarmen och säger att de kommer från säkerhetspolisen. Överste Stig Wennerström är anhållen för spioneri.

Foto SCANPIX CODE 20360

During the 1950s, Swedish air force Colonel Stig Erik ‘The Eagle’ Constans Wennerström leaked Swedish air defence plans, including a wealth of information about Saab Draken fighter jet project, to the Soviet Union. Security forces suspected him and employed his maid as an agent who discovered rolls of films hidden in his house. Despite Wennerström’s treachery the Draken emerged as a remarkably effective machine. The wing was an absolute masterpiece of aerodynamics, an avant-courier of the LERX of the later F-16, MiG-29 and Hornet which gave the aircraft performance far exceeding the expectations of international observers. On half the installed the thrust of a Lightning, the Draken offered similar performance, three times the air-to-air missile weapon load and a far longer range. Not only that, it managed to achieve this remarkable performance with fixed air intakes, a fact that is often overlooked.

Video: Saab J35 Draken trainers doing the Swedish Cobra Maneuver

Then there’s the ability to ‘cobra’ by turning off the flight control limiters, known to the Swedish pilots who discovered this as “kort parad”, or “short parry“. And there’s the infra-red sensor – and the datalink. All of which added up to a remarkable whole. The Draken was a masterpiece of strategic thinking, aeronautical design and engineering.

Source: hushkit.net