Please use the sharing tools found via the share button at the top or side of articles. Copying articles to share with others is a breach of FT.com T&Cs and Copyright Policy. Email [email protected] to buy additional rights. Subscribers may share up to 10 or 20 articles per month using the gift article service. More information can be found at https://www.ft.com/tour.

https://www.ft.com/content/e6a2fcff-c2fb-411f-a594-6b88a17ffdf7

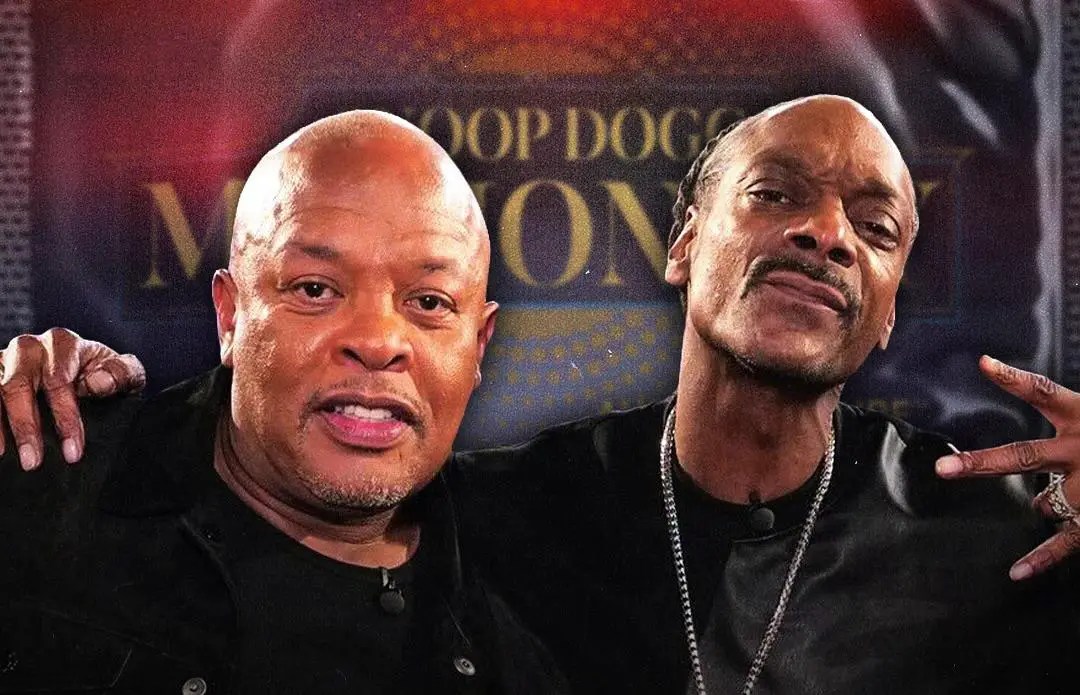

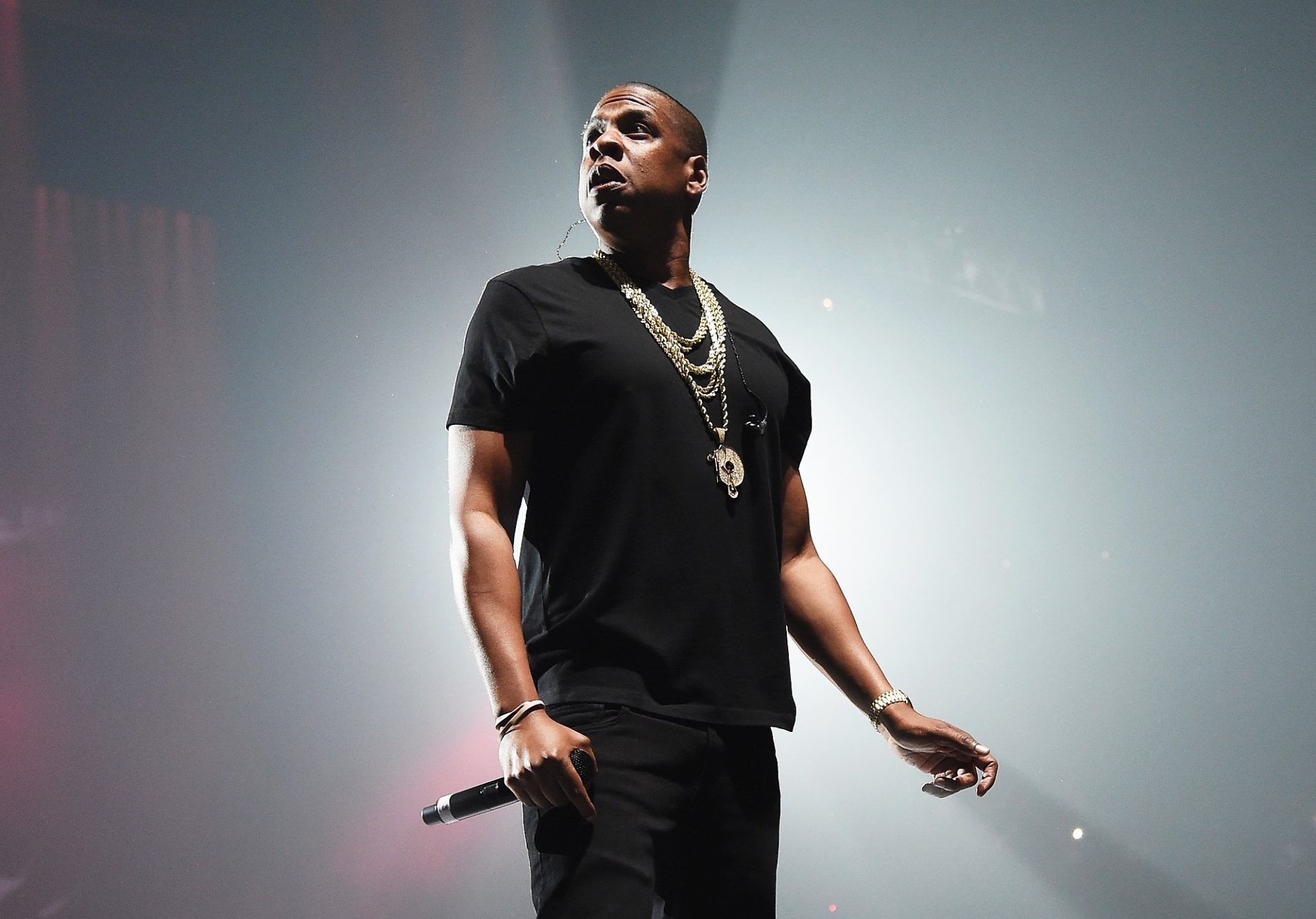

It has been another busy week for Jay-Z, the hip-hop musician and entrepreneur. On Monday, he unveiled a deal with LVMH to expand his Armand de Brignac champagne globally. The next day, Oatly, the Swedish vegan-milk group in which he has invested, took its first step towards a $10bn initial public offering.

Jay-Z has further tasks to occupy him, apart from his own music. He still heads Roc Nation, a music and sports talent agency that includes Rihanna among its clients. He is also “chief visionary officer” of a special-purpose company backed by Roc Nation that acquired two Californian cannabis groups in November. And so on.

This year is the 25th anniversary of Jay-Z’s first album Reasonable Doubt, released on his own Roc-A-Fella Records label. The rapper, born in Brooklyn as Shawn Carter and declared the first hip-hop billionaire by Forbes magazine in 2019, has since poured his talent and wealth into so many ventures that it is easy to lose track.

Some have lasted and some not, but Jay-Z was ahead of his time in business in a way that is only now clear. “Put me anywhere on God’s green Earth, I triple my worth,” he once rapped. The deal with LVMH, under which the world’s leading luxury group has taken 50 per cent of Armand de Brignac — the “Ace of Spades” champagne praised in his lyrics — is proof of that.

He learnt early from Damon Dash, the impresario co-founder of Roc-A-Fella, that a celebrity could not only be paid to perform songs or endorse products but might also own the rights to both. It was a glaring opportunity for early hip-hop artists because they were walking, rhyming advocates of luxury, lauding everything from Mercedes-Maybach limousines to Cristal champagne.

Jay-Z accepted an offer from Universal Music to head Def Jam, parent of Roc-A-Fella, in 2004 partly because it enabled him to regain the rights to his master recordings — ultimate ownership of his work. “I could say to my son or my daughter . . . ‘Here’s my whole collection of recordings. I own those, they’re yours.’” he said.

It was astute even then, but the point of musicians owning their masters has only fully emerged in the age of streaming, which makes it easier to listen to all of an artist’s work. Both Taylor Swift and Kanye West, who produced and recorded for Roc-A-Fella, have demanded their masters back — but Jay-Z has his already.

Please use the sharing tools found via the share button at the top or side of articles. Copying articles to share with others is a breach of FT.com T&Cs and Copyright Policy. Email [email protected] to buy additional rights. Subscribers may share up to 10 or 20 articles per month using the gift article service. More information can be found at https://www.ft.com/tour.

https://www.ft.com/content/e6a2fcff-c2fb-411f-a594-6b88a17ffdf7

He launched his own sneaker line — S. Carter for Reebok — in 2003, following one role model, the basketball player Michael Jordan. But the turning point for his attitude to endorsement came in 2006 when a French executive at Louis Roederer, maker of the Cristal champagne extolled by rappers, indicated that it would rather not be associated with hip-hop.

Jay-Z swiftly denounced the remarks as racist and declared, “[I] will no longer support any of his products”, Zack O’Malley Greenburg records in Empire State of Mind, a book on Jay-Z’s businesses. He was as good as his word: soon afterwards, he appeared in a music video spurning a waiter’s offer of Cristal in favour of a metallic bottle of Ace of Spades.

His financial interest in Armand de Brignac, a wine produced by the Cattier family in Montagne de Reims, was obscure at the time — he seems to have thought it better not to be seen hawking his own wares. But it was clearly worth his while and in 2014, he acquired rights to the brand from its US distributor Sovereign Brands.

That makes this week’s deal significant in two ways. It indicates that he has managed to nurture his prestige tipple, which sells for $300 a bottle or more, through the pandemic wedding and nightclub drought. It also shows that French luxury houses no longer shy away from rap: they now want to partner with black artists.

It took a long time. “We came out of the generation of black people who finally got the point: no one’s going to help us . . . Not even our fathers stuck around,” he wrote in his autobiography Decoded. “Success [meant] self-sufficiency, being a boss, not a dependent. The competition wasn’t about greed — or not just about greed. It was about survival.”

Rihanna, whom he personally signed to Def Jam when she was 17, has learnt from his philosophy by launching her Fenty Beauty brand with LVMH, and her Savage X Fenty lingerie line. Like him, she has also had disappointments — the fashion house she formed with LVMH in 2019 suspended its ready-to-wear collections in February.

But occasional failure is part of the hustle, and the striking thing about Jay-Z is not his missteps but how accurately he sensed how the world would evolve. Every Instagram influencer endorsing cosmetics, fashion or travel owes something to the performative consumption pioneered by hip-hop.

“The rapper’s character is essentially a conceit, a first-person literary creation,” he observed of his original transformation from Shawn Carter to Jay-Z. He understood sooner than others the need to own a performance as well as performing — to be the brand, not work for one. That calls for champagne.