California startup JetZero says it’s working with the USAF, NASA and the FAA to get a blended-wing body jet airliner into service by 2030, promising to use an astonishing 50% less fuel, and providing a perfect platform for clean hydrogen airliners.

A high-lift blended wing body airliner would use half as much fuel as today’s airliners for the same payload, says Jet ZeroJetZero

A high-lift blended wing body airliner would use half as much fuel as today’s airliners for the same payload, says Jet ZeroJetZero

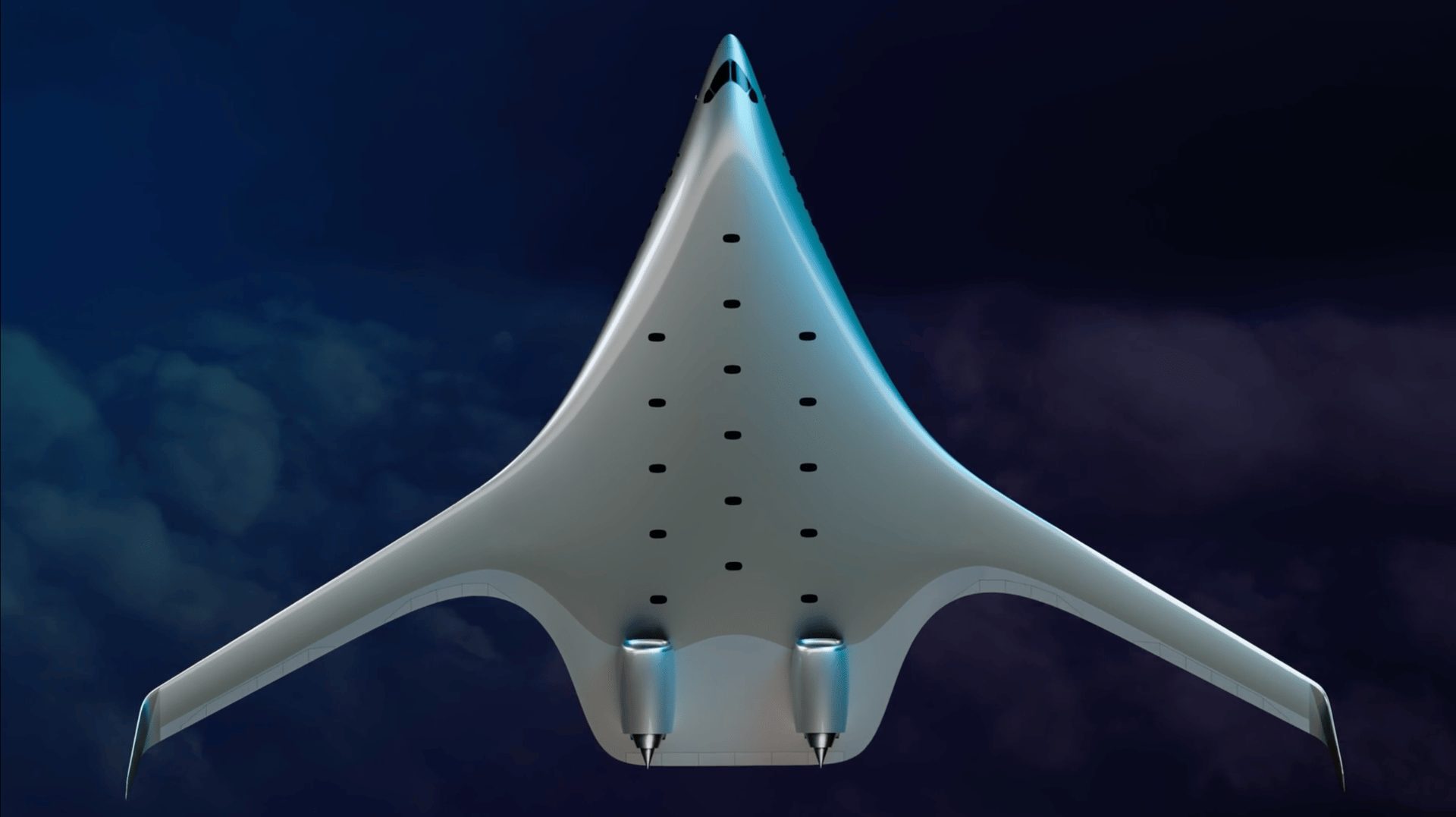

We’ve written many times before about blended wing designs – Airbus, NASA and Boeing are among the companies that have built and flown demonstrators, but none have committed to bringing one through into service. Halfway between a full flying wing design and a traditional airliner shape, a blended wing body uses a wide, flattish fuselage that smoothly blends outward into a pair of wide wings, with no clear dividing line separating the wing from the body.

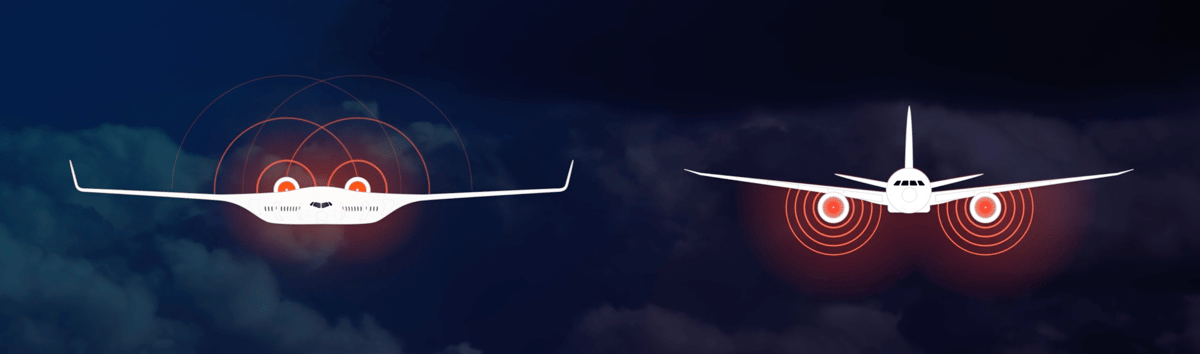

There are several benefits: the fuselage itself can contribute much more lift than a typical tube shape, so you don’t need as much wing surface. It’s aerodynamically stable, so you don’t need a tail wing, and these factors add up to dramatic reductions in drag and weight, leading to smaller engines and further weight savings. There’s a heap more room inside for cargo and passengers, with a seating layout that starts looking more like a theater than a regular airliner. And the engines can be mounted topside, resulting in much lower noise both in the cabin and on the ground.

Much lighter, with higher lift and lower drag, the blended wing design also places its (smaller) engines on top, significantly reducing noise both in the cabin and on the ground below JetZero

Much lighter, with higher lift and lower drag, the blended wing design also places its (smaller) engines on top, significantly reducing noise both in the cabin and on the ground below JetZero

When it comes to clean, hydrogen-powered aircraft, the extra storage space out toward the wings is perfect for carrying hydrogen tanks, which are lightweight but take up a lot of space. Indeed, a blended wing concept was one of the three Airbus presented as hydrogen-fueled future airliners back in 2020.

In terms of drawbacks, the wingspan is wider than a typical airliner, which can restrict the number of airport bays they’ll fit into if they don’t run fold-up wings. They’re harder to evacuate, and passengers out toward the sides experience quite a rollercoaster when the plane banks since they’re further out from the roll axis. They require much more of a redesign than a winged tube shape if you’re looking to change the size, and window seats – if you decide to run windows at all – become a rare treat.

While both NASA and Airbus reported about a 20% reduction in fuel consumption with their prototypes, JetZero reckons they’re underselling things.

“The blended wing is 50% more efficient. Yes, that’s what I said: 50%,” says Founder Mark Page. “It uses half the fuel, makes half the carbon dioxide compared to a tube-and-wing aircraft, frankly, even with the same engines. Fuel is the largest line item on an airline’s profit and loss statement. A JetZero blended wing cuts that line item in half. That’s not just a competitive advantage; in the future, it’ll be survival.”

While its wingspan would be larger than a 767, JetZero says the A-5 will be capable of operating at any airport that can handle an A330 JetZero

While its wingspan would be larger than a 767, JetZero says the A-5 will be capable of operating at any airport that can handle an A330 JetZero

Page and some of his JetZero colleagues worked on a blended-wing demonstrator project in the 1990s, as a partnership between NASA, McDonnell Douglas and Stanford University. Indeed, Page claims he shares credit with Bob Liebeck and Blaine Rawdon, two of JetZero’s technical team, for inventing the blended wing concept. According to an interview with Aviation Week, the company is now ready to come out of “stealth mode” and try to get an aircraft built, tested, certified and into service by 2030, with a NASA-supported 1/8th-scale demonstrator preparing to fly later this year.

The first JetZero aircraft, should there ever be one, will be the Z-5. It’s designed to replace the Boeing 767, aiming to carry at least 250 passengers and to offer a range over 5,000 nautical miles (5,754 miles, 9,260 km). While the 767’s wingspan goes to around 170 ft (52 m), the Z-5 will be nearly 200 ft (61 m) wide. It’ll still work, though, at any airport that can handle an Airbus A330. It’ll use off-the-shelf engines, requiring nothing particularly special.

Now, this is all well and good to talk about, but according to Pitchbook, JetZero is sitting on a war chest of just US$4.55 million in early stage venture capital. Airbus, on the other hand, brings in nearly US$60 billion a year, already owns a lot of the stuff you need to build airplanes, and has more than 126,000 employees to throw at an idea like this if it feels it’s worthwhile. So how does JetZero hope to overcome such monolithic competition?

JetZero has put the Z-5 forward for a US Air Force in-air refuelling development program that may make a sizeable contribution to development funding JetZero

JetZero has put the Z-5 forward for a US Air Force in-air refuelling development program that may make a sizeable contribution to development funding JetZero

Well, possibly by gnawing at the thickly calloused teat of the US military. According to Air & Space Forces Magazine, JetZero has applied for a US$245-million Air Force blended-wing demonstration program, which would get a full-scale Z-5 demonstrator airborne by 2030, with a view to potentially replacing the 767-derived KC-46 tanker as part of the USAF’s Next Generation Air Refueling System (NGAS).

“We’re not just building an airliner,” says Page, “we’re building a multi-mission platform. A platform that can best the best-in-class in every market. Airliner, freighter, tanker. The US Air Force is interested in this aircraft as a tanker. Remarkably, the JetZero tanker burns only half the fuel of existing tankers today.”

The winning proposal is due to be selected this summer.

Clearly, every step of this company’s ambition represents a colossal challenge, from fundraising, to design, testing, certification and manufacturing. Just the idea of starting a new airliner company from scratch, built around a technology that’s well known to the big players in the industry, but that seems to have been tried and shelved again and again, boggles the mind – let alone doing it all in time to get something into commercial service by 2030. That just seems wildly fanciful.

Founder Mark Page and other JetZero team members claim they invented the blended wing concept, and built a demonstrator in the 1990s as part of a partnership between NASA, McDonnell Douglas and Stanford University JetZero

Founder Mark Page and other JetZero team members claim they invented the blended wing concept, and built a demonstrator in the 1990s as part of a partnership between NASA, McDonnell Douglas and Stanford University JetZero

But Barry Eccleston, former Airbus Americas and International Aero Engines CEO and current member of JetZero’s star-studded advisory board, says the timing may just be right.

“You have all these tailwinds from the environment, the Air Force and NASA, plus you have the technology tailwind, which makes it viable when it wasn’t before,” he tells Aviation Week. “Then you set that against the fact that Boeing and Airbus are doing nothing new in this space and you say, ‘We can’t sit here and do nothing.’ The industry deserves it, and the industry needs it. If you’ve got something you know will be 30-50% better than today’s products, why would you not do it?”

Why indeed? We’d love to see it happen.

Sources: JetZero, Aviation Week, Air & Space Forces Magazine