It is December 1968, and a truly ground-breaking airliner is about to take its first flight. It resembles a giant white dart, as futuristic an object as anything humanity has made in the 1960s. The aircraft is super streamlined to be able to fly at the speed of a rifle bullet – once thought too fast for a passenger-carrying aircraft.

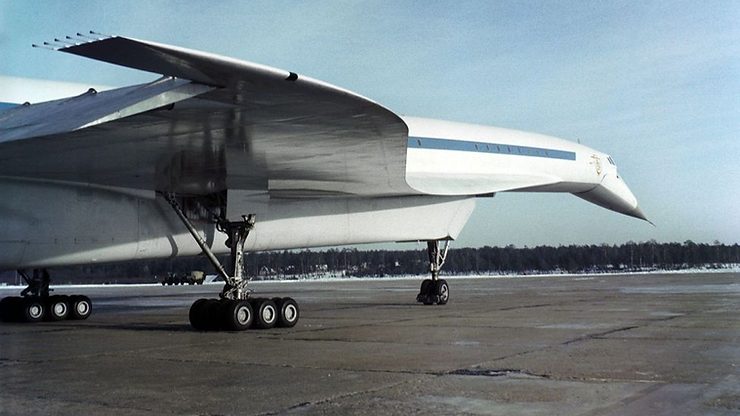

The distinctive, needle-nosed front of the aircraft looks like the business end of something rocket-powered from a Flash Gordon serial; when the aircraft approaches the runway, the whole nose is designed to slide down, giving the pilots a better view of the ground. The effect makes the aircraft look like a giant bird about to land.

It sounds like a description of the Anglo-French Concorde, the plane that will cross the Atlantic in little more than three hours – but it’s not. The spaceship-styled jet sports the hammer and sickle of the Soviet Union on its giant tail-fin. It is the Tupolev Tu-144, the communist-built Concorde, and the first passenger aircraft to fly more than twice the speed of sound.

Its first flight comes three months before Concorde takes to the air. But the Tu-144 – dubbed ‘Concordski’ by Western observers for its similarities to its luxurious rival – never quite becomes a household name.

It is partly down to design failure – but also because of a high-profile disaster at the 1973 Paris Air Show, a tragedy that took place in front of the world’s media. Like many of the great technological feats during the Cold War, politics is at the heart of the Tu-144’s story.

In 1960, Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev was made aware of a new aircraft project being investigated by Britain and France to help revitalise their aircraft industries. That passenger aircraft – Concorde – was designed to fly at supersonic speeds, cutting the time it would take to fly from Europe to the US to just a few hours. Two years later, the British and French signed an official deal to begin design and manufacture. Around the same time, supersonic transport (SST) projects from manufacturers Boeing and Lockheed were also given the go-ahead.

In the 1950s, the USSR’s rapid industrialisation led Soviet planners to demand ever-more impressive projects. Adding to the laurels of the Soviet space programme and Soviet military aviation, it appealed enormously to leaders mesmerised by the very real achievements of their leading-edge industries. This tension between Soviet technical and economic reality and the heightened expectations of the Soviet elite that commissioned it explains much of its subsequent complex history

The Tu-144 project became something that had to succeed, regardless of the effort required to bring it. And in the 1960s, with so much of the Soviet technical resources thrown into the space race, that was not inconsiderable. The space race undermined the Tu-144 programme by shifting the Soviet focus towards long-range rocketry and high-altitude missiles, and away from supersonic bombers, effectively forcing the Soviets to develop the Tu-144 as a standalone civil aircraft programme.

This ran counter to Soviet experience in creating airliners and left the developers with the hugely ambitious task of designing from scratch a complex supersonic aircraft which could also satisfy requirements for comfort and economic performance, requirements which had seldom been necessary to consider.

Several problems soon came to plague the Tu-144. It was a project perhaps 10 to 15 years ahead of what the Soviet aviation industry was capable of at the time. Two of the main areas where the Tu-144 lagged behind were brakes and engine control.

Concorde pioneered some truly leading-edge technologies, not least with its brakes. It was one of the first aircraft to have brakes made of carbon fibre, which could withstand the enormous heat generated trying to slow the aircraft after landing.

An even bigger problem was the engine. Concorde was the first passenger aircraft to have a flight-vital part of its system completely controlled by a computer, it would constantly change the shape of the air inlets to ensure the engines were operating as efficiently as possible. Concorde also had a flight control system that could adjust, ever so slightly, the shape of the wing to reduce drag as it flew at supersonic speeds. Such computer-controlled wings were unheard of before Concorde.

Aware that Concorde was slowly but methodically taking shape, the Soviet Union poured more and more resources into the Tu-144. It is something of a testament to the Tupolev design bureau – and the teams from engine designers Kuznetsov and Kolesov, who both built power plants for the ambitious new airliner – that amid the enormous effort to match the American space programmes, they still managed to build such a plane.

While the Tu-144 was more powerful, it also took more effort to get into the air. Empty, the Tu-144 weighed a few hundred kilograms under 100 tonnes – more than 20 tonnes heavier than an empty Concorde. Part of this was due to the enormous undercarriage. Concorde had two wheels at the front and two sets of four wheels underneath the wings. The Tu-144 had two at the front but 12 underneath the wings, partly because Russian tyres were made of synthetic rubber and were more prone to failure, the thinking being that if one or two failed, there would be enough to support the aircraft’s weight.

While on the surface the Tu-144 looked very similar to Concorde, there were many differences, many of them less sophisticated solutions to the problems Concorde’s designers had also solved.

The USSR, however, won bragging rights over who got to fly a supersonic airliner first. The Tu-144 first took off in December 1968 and flew supersonic for the first time in June 1969. Concorde would not take to the air until March 1969 and did not go supersonic until October of that year. The Soviets had won a major diplomatic coup but they soon encountered a series of headaches trying to get the nearly 100-tonne airliner into service.

Western observers used to the perceived superiority of technology west of the Berlin Wall, believed that the only way the Soviet Union could have come up with the Tu-144 was through industrial espionage; the Tu-144 was dubbed ‘Concordski’, and regarded as an almost carbon copy of Concorde, though with a cruder Soviet finish.

The truth, says Kamisnki-Morrow, wasn’t quite so clear cut. “There is no doubt that Soviet thinking on the Tu-144 was heavily influenced by Concorde – the absence of a horizontal stabiliser, for example, was a radical departure from previous Soviet designs.”

Other aspects, such as the engine configuration, were notably different. The Tu-144 also needed to be more rugged to cope with tougher operating conditions. Although espionage played a role in the Tu-144’s development, the Soviets were still capable of exploring their own avenues to solve the multitude of technical problems thrown up by the project. The result was an aircraft which broadly resembled Concorde but which differed substantially in refinement and detail.

In 1973, the Soviets unveiled the Tu-144 to the West at the Paris Air Show. Tupolev flew the second of their production models to the airshow, pitting it head-to-head against a prototype Concorde already carrying out public flying displays.

The rivalry between the two supersonic airliner teams was immense. “Just wait until you see us fly,” Tu-144 test pilot Mikhail Koslov apparently taunted the Concorde team, according to Time magazine. “Then you’ll see something.” On 3 June the Tu-144 took to the air, with Kozlov seemingly intent on surpassing Concorde’s flying display the day before, which had been somewhat cautious. Then disaster struck.

The Tu-144 took off, then approached the runway as if to make a landing, with its nose drooped and its undercarriage down – then climbed rapidly, with its engines at full power. Seconds later, it pitched over, broke up in the air and dived into a nearby village. All six of the crew and eight people in the village were killed.

There were several theories as to why the Tu-144 crashed; some believed the pilot had manoeuvred too hard at a slow speed, causing the plane to lose lift. Others said the cloudy conditions might have confused the crew. Another theory was the plane had, at the last minute, had to swerve to avoid a French Mirage fighter jet that was flying close to take pictures of the Tupolev’s front canards, which were advanced for the time.

The crash only highlighted some ongoing issues with Tupolev’s pioneering design and the Soviet State airline Aeroflot started to get nervous about bringing it into full service. Tupolev had to fix a myriad of issues before the aircraft could be signed off for service. Even then, the first airline flights in 1975 were still essentially test runs, carrying mail instead of passengers from Moscow to what is now Almaty in Kazakhstan.

The Soviets couldn’t find an elegant solution to reducing noise inside the passenger cabin. The engines, and the air conditioning units which drew air from the engine inlets, both created enormous noise. Air conditioning was vital, the cabin would otherwise have become dangerously hot from the heat generated by air friction on the plane’s skin. Concorde used its fuel as a ‘heat sink’ to keep temperatures down, so didn’t need such powerful air conditioners, this kept the noise down to acceptable levels.

Tupolev had brought the Tu-144 into the air, but once in service, it seemed that the plane was more trouble than it was worth. The intensely political project had chewed through enormous resources. In 1977, Tupolev tried to buy some of the engine management computers Concorde used, but the British, fearing they could also be used on Soviet jet bombers, refused.

What had been one of the Soviet Union’s prized technological feats became a political hot potato. Aeroflot did not even make any reference to the aircraft in its five-year plan from 1976 to 1982. After a modified Tu-144 crashed on a pre-delivery test flight in June 1978, Aeroflot pulled the plug on the Tu-144’s airline career. It had flown only 102 commercial flights, and only 55 of those had carried passengers. Concorde, in comparison, flew for more than 25 years, racking up thousands of flights and becoming one of the most iconic designs of the 20th Century.

The Tu-144’s production officially ended in 1982. The 14 remaining Tu-144s had a brief second life, training crews for the planned Soviet space shuttle, the Buran. By the time the Berlin Wall fell in 1989, the remaining models were mostly mothballed, a few of them in storage at the Soviet aircraft testing base at Zhukovsky, near Moscow.

In the 1990s, NASA began a multi-billion-dollar project to build the next generation of supersonic transports, called the High-Speed Research (HSR) programme. Boeing and Lockheed had started building Concorde-like designs in the 1960s but they had been cancelled for various reasons, including fuel costs and noise concerns. Now, nearly 30 years later, NASA hoped to pick up from where those projects left off.

Because the US had never built a supersonic airliner, its own plans in the 20th Century had fallen through and NASA needed help from elsewhere to carry out flight tests. There was one big problem, neither British Airways nor Air France had a spare Concorde that they could use for experiments.

The Soviet Union had collapsed only a few years before. Russia was in dire shape, with its economy in free fall. Russia did have a supersonic airliner – albeit one that had had a chequered career and was no longer flying. An agreement was made in 1993 to lease a Tu-144 a do a number of very sophisticated experiments. It was not easy to do business in Russia, the Tupolev had to be leased by a British company, IBP Aerospace, a contractual company that could act as a go-between.

The Tu-144 leased by NASA was fitted with more reliable, modern engines and a whole suite of instruments, including a special ‘data bus’, one which could store all the data from the many experiments running as the plane flew its missions. However, the early flights were a disaster in terms of data collection. The data bus recorded impossible flight characteristics. The Russian pilots, flying the plane on behalf of Tupolev, couldn’t be interviewed by NASA. Interviews with the pilots hadn’t been written into the contract. It was decided that NASA would have to send its own pilots to test the Tupolev.

Robert Rivers and Gordon Fullerton (who died in 2013) were chosen to fly the Tu-144 on a series of flights through to the end of 1998. By the end of it, Rivers was the only person on Earth who could lay claim to first-hand experience flying both the Tu-144 and its Western competitor. He says he could not have done it without the assistance of the Russian flight crew, pilot Serge Boresov, navigator Viktor Pedos and flight engineer Anatoli Kriulin, whose expert knowledge helped make the flights a success.

The NASA flights spelt the end of the Tu-144’s flying career. Despite the refinements added with Western help, the aircraft was too expensive and unreliable to fly passengers once more. The remaining ‘Concordskis’ are now in museums or stored in hangars. One now stands outside a technical museum in Germany, right next to an example of its old rival.